# fundamental skills and knowledge you must have in 2026 for SWE

Table of Contents

These notes are based on the YouTube video by Geoffrey Huntley

Key Takeaways

- LLMs can assist with reverse‑engineering and “clean‑room” style analysis – By feeding only assembly to an LLM you can often obtain a high‑level description of the program’s behavior, and then ask the model to generate code for a different architecture (e.g., Intel → Sinclair Z80). However, research up to early 2026 shows that open‑source LLMs still struggle with accurate name recovery and type inference without fine‑tuning, so the results are best‑effort rather than guaranteed.

- Ralph – a simple bash loop that repeatedly calls an LLM (the “agent”) to perform tool calls, generate specs, and iterate. Running Ralph for 24 h with a modern hosted model typically costs on the order of $8–$12 / hour (depending on the provider’s pricing and the model size). This makes AI‑augmented development cheaper than many low‑skill manual jobs, but the exact figure should be verified against current API rates.

- Business moats are shifting – If a small, well‑equipped team can clone a SaaS product’s core feature set in weeks rather than months, traditional advantages (size, brand, licensing) erode. Infrastructure (proprietary data pipelines, low‑latency compute, secure tool‑call frameworks) may become the most durable moat.

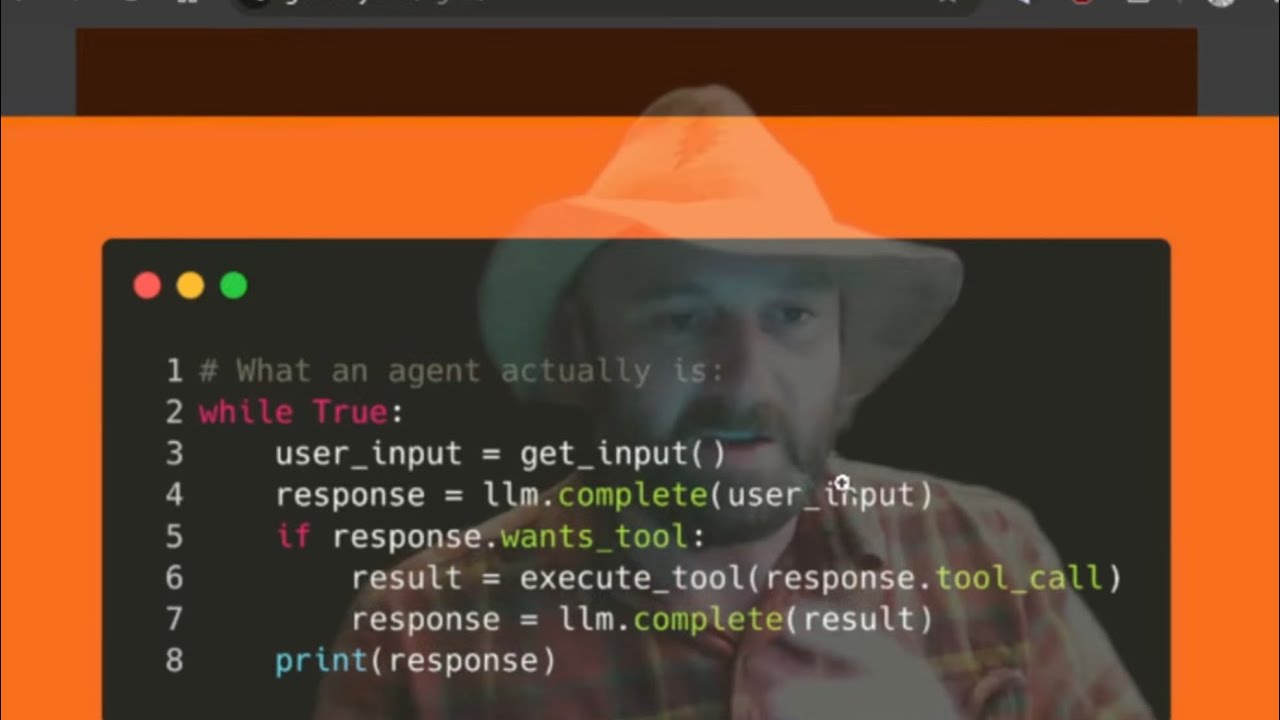

- New baseline skills for 2026 SWE roles – Understanding the inferencing loop, tool calls, and how to build a coding agent are now as fundamental as linked‑list knowledge was a decade ago, but the community still treats these as emerging competencies that are being formalized in curricula and workshops.

- Hiring focus is evolving – Recruiters are beginning to prioritize candidates who can demonstrate agent construction, tool‑registration, and loop‑design on a whiteboard, especially for roles that involve AI‑augmented development. The shift is noticeable but not yet universal across all tech firms.

- Corporate transformation lag – Large enterprises’ multi‑year AI adoption programs often trail “model‑first” startups that can iterate in weeks. The gap is real, though some forward‑looking corporations are accelerating their roadmaps through dedicated AI labs.

Important Concepts Explained

1. The Z80 Experiment (illustrative case)

- Goal: Show that a language/CPU‑agnostic LLM could reconstruct a program’s intent from raw assembly and then re‑target it to a completely different platform.

- Process (as reported by the presenter):

- Write a simple C program (sales‑tax calculator).

- Compile to binary → decompile to assembly.

- Delete source and binary, leaving only assembly.

- Prompt an LLM (Sonnet 3.5 at the time) to study the assembly and output a high‑level specification.

- Feed the spec back to the model and ask it to generate a Sinclair Z80 version.

- Result: The presenter demonstrated a working conversion, which serves as a proof‑of‑concept that LLMs can act as a “clean‑room” reverse‑engineering aid. No independent replication of this exact cross‑architecture conversion has been published, so treat the experiment as an illustrative example rather than a universally reproducible benchmark.

2. Ralph – The Looping Agent

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| LLM (e.g., Sonnet 4.5) | Generates code/specs, interprets tool results |

| Bash script | Executes a system call to the LLM, appends responses to an array, and repeats |

| Tool calls | External functions (read file, list directory, run bash command, etc.) that the LLM can request during inference |

| Array (memory) | Stateless storage; each turn appends the new interaction, mimicking a “conversation log” |

Ralph’s workflow (simplified):

while true; do response=$(curl -s -X POST $LLM_ENDPOINT -d "$PROMPT") echo "$response" >> conversation.log if [[ $response == *"tool_call"* ]]; then execute_tool "$response" fi PROMPT=$(prepare_next_prompt conversation.log)done- Forward mode: Generate specs → code → run.

- Reverse mode: Feed compiled artifacts → ask LLM to infer specs (clean‑room reverse engineering).

⚠️ Security Note

Continuous loops that execute tool calls based on LLM output are vulnerable to prompt‑injection and sandbox‑escape attacks. In production you should validate every tool request, enforce strict I/O whitelists, and consider running the agent inside a hardened container. (See recent 2026 security studies on LLM‑driven agents.)

🔗 See Also: LLM Security Best Practices

3. Clean‑Room Design & Reverse Engineering

- Historical analogy: AMD’s early CPUs were built from “clean‑room” specs reverse‑engineered from Intel’s designs. The engineer who produced the specs was barred from working on the product (golden handcuffs).

- Modern application: An LLM in reverse mode can produce a specification document from publicly available binaries or documentation, enabling a team to develop a compatible implementation without directly copying protected source code. Because current models have limited accuracy on low‑level name and type inference, the output usually requires human verification and, in many cases, additional fine‑tuning or prompting tricks.

4. Economic Implications

- Cost of AI‑driven development: Running a high‑performing hosted LLM continuously for 24 h typically costs ≈ $8–$12 / hour (e.g., Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 or OpenAI’s GPT‑4o pricing as of Jan 2026). On‑premise inference on a modest GPU cluster can be cheaper per hour but adds hardware‑maintenance overhead.

- Unit‑economics shift: Software development can become cheaper than many low‑skill manual jobs (e.g., fast‑food work), but the exact break‑even point depends on the complexity of the task, the model’s token usage, and the cost of any required tooling.

- Moat erosion:

- Feature‑set cloning can be accelerated to weeks for a well‑organized two‑person team using agentic workflows, not “days” in most realistic scenarios.

- Traditional competitive advantages (large engineering orgs, proprietary code) lose relevance when the core development pipeline is AI‑augmented.

- Infrastructure (proprietary data pipelines, low‑latency compute, secure tool‑call orchestration) may be the only defensible moat left.

5. Baseline Technical Knowledge for 2026

| Skill | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Inferencing loop | Core of any LLM‑driven system; you must understand how prompts, responses, and state are managed. |

| Tool‑call architecture | Enables LLMs to interact with the external world (file system, APIs, shells). |

| Agent construction on a whiteboard | Demonstrates a mental model of loop, state, and tool integration – the new “linked‑list” interview test. |

| Context‑window management | Knowing how to chunk data, summarize, and feed back into the model is essential for scaling agents. |

| Basic harness code (≈ 300 LOC) | All major coding assistants (Cursor, Code‑Llama, etc.) reduce to a few hundred lines that orchestrate the loop. |

| Understanding of “agentic” vs. “thinking” models | Agentic models (e.g., Sonnet, Opus) can plan and invoke tools; “thinking” models (e.g., GPT‑3.5) require external orchestration. |

| Security & sandboxing basics | Recent research shows prompt‑injection and tool‑call abuse are real threats; engineers must know how to mitigate them. |

🔗 See Also: Claude Code’s New Native Skills Just Changed Everything

6. Hiring & Career Implications

- Preferred candidate profile (emerging trend):

- Can draw the inferencing loop on a whiteboard.

- Knows how to register and invoke tools (read, list, bash, edit).

- Has built a simple coding agent (≈ 30 min workshop) and can discuss its safety mitigations.

- Risk landscape: Senior engineers who have not adopted agentic tooling may find their skill set de‑valued relative to junior engineers who have spent six months building and hardening agents. The shift is noticeable but not yet universal; many firms still prioritize classic data‑structure expertise alongside the new skills.

- Job market dynamics:

- Large enterprises often run 3–4 year AI transformation programs, which can be outpaced by “model‑first” startups that iterate in weeks.

- Startups founded in lower‑cost locales and built around lightweight agentic pipelines are beginning to dominate early‑stage venture funding rounds in 2026.

7. Workshop Highlights – “How to Build an Agent”

- Tool registration – Define a JSON schema for each tool (name, description, parameters).

{"name": "read_file","description": "Read contents of a file","parameters": {"type": "object","properties": {"path": {"type": "string"}},"required": ["path"]}}

- Loop skeleton – ~300‑line harness that:

- Sends user prompt + tool list to the model.

- Parses the model’s JSON‑encoded tool call.

- Executes the tool locally, appends output to the conversation array.

- Re‑sends the updated array for the next turn.

- Typical tool chain –

list,read,write,bash,edit. Combining these yields a full‑featured coding assistant.

💡 Related: Claude Code Agents: The Feature That Changes Everything

Summary

Geoffrey Huntley’s talk illustrates a paradigm shift: LLMs are now capable of assisting both reverse‑engineering and cross‑architecture code generation, though the process still requires human verification and, in many cases, model fine‑tuning. The simple “Ralph” loop shows that a modest compute budget can automate large portions of the software development cycle, dramatically lowering costs and eroding traditional competitive moats in SaaS.

Because of this, the core competencies for software engineers in 2026 have moved from classic data‑structure mastery to agentic thinking: understanding the inferencing loop, registering and orchestrating tool calls, building lightweight harnesses, and—critically—hardening those systems against prompt‑injection and other security risks. Recruiters are beginning to prioritize these abilities, and engineers who fail to adopt them risk rapid obsolescence.

Practical takeaway: Learn to build and reason about coding agents now—the workshop material, the ~300‑line harness, and the tool‑call patterns are the new fundamentals that will determine who thrives in the AI‑augmented software landscape.

🔗 See Also: Agentic Workflows Overview

🔗 See Also: Claude Code Agents: The Feature That Changes Everything